On Hacking Fluent Forever To Learn Languages Faster

Update 10/27/2022: This is an older post written before we launched our proprietary language app and Live Coaching program. Based on our proven 4-Step Method, these products now offer you a faster route to fluency than was possible before.

Check out our products page to download the latest app version and sign up for Coaching.

Today, I’m going to talk about the first major revision to the methods presented in Fluent Forever. I’ve been wanting to share this stuff for a long time, and it seems like today’s the day when I actually have the time to write about it. Yay!

Background: Why the change?

The methods I wrote about in Fluent Forever came out of a lot of trial and error. I’d start on a language, try some stuff, see what worked or didn’t, and adjust my approach accordingly.

Once I started writing the book, I had a year or two to do intense research. That gave me a chance to understand why things worked or didn’t, and to tweak my methods accordingly.

It also gave me a chance to think about whether there was a way to break my method down into steps that were easier to follow and more effective than simply: “Hey, go make a bazillion flashcards and learn all the things!”

This turned out to be a good plan, and I was proud of the finalized, polished method that came out of that: 1. Learn Pronunciation, 2. Learn Simple Vocab, 3. Learn Grammar, 4. Play. I used it exactly as written to learn Hungarian, and felt really good about the results.

Then I tried Japanese.

Japanese was, well…a pain. This was partly due to challenges in the language itself, and partly due to timing – I needed to learn it faster than was possible.

The language: Japanese is hard. Really hard. And that’s almost entirely due to the existence of Kanji, the Chinese characters adopted into Japanese.

Kanji characters are jerks. They don’t like being memorized, and at this point, after a lot of trial and error, I’ve found some good ways to use flashcards and mnemonics to memorize them.

(If you’re curious about all that, start here, then go here and here. And this post and this one are handy, too.)

Timing: For the purposes of our present discussion, timing ends up being more important than Kanji. I got myself into a bit of trouble with Japanese. I had planned to start in December of 2014 and go to Middlebury’s Immersive Japanese school in June. I figured that in those 7 months, I’d be able to land myself in level 2 (of 4), or, if I really pushed it, level 3.

But I wasn’t willing to start until I had finished my Japanese Pronunciation Trainer, since that somehow seemed karmically fair to my Kickstarter backers, who were also waiting for me to finish that trainer (along with the others). And I didn’t get a working version of my Japanese Trainer until mid-March.

Now I had 3 months to get myself into level 2 at Middlebury. Shitshitshit.

Fluent Forever says to learn pronunciation, then simple vocab, then grammar. If I had stuck to the original Fluent Forever guidelines, I’d have gotten through ~400 simple vocabulary words by the time I arrived at Middlebury. I would have shown up at their placement test, where I was supposed to be able to write basic Japanese and have simple conversations about myself and restaurants and travel plans, and instead of being able to do any of those things, I would have the ability to stand up and say “立つ!” (STAND!). Then I could point at a table and say “テーブル!” (TABLE!) and look at a glass of water and say “水!” (WATER!). And I would be able to write those out in Kanji, using super-awesome mnemonics! And I would have good pronunciation! And I’d be thinking in Japanese!

And the Middlebury faculty would say, “That’s nice,” and place me in level 1 with the students who hadn’t yet studied any Japanese at all.

I needed to arrive there with some grammar, whether my book says I should wait on that or not.

(Historical side note: Shortly before June, I realized that there was no way I could go to Middlebury and continue progress on the Kickstarter project, and I didn’t feel comfortable putting the Kickstarter stuff on hold for 8 weeks. I ultimately decided to withdraw from Middlebury and spend the summer working. Relevant to our discussion here, that decision was also influenced by the fact that my Japanese was going really well, all on my own.)

The big change: Combining Steps 2 (simple words) and 3 (grammar) with the help of a tutor

I began with pronunciation, as normal, using my Japanese Pronunciation Trainer. (I also learned ~50–60 Kanji radicals.)

I then grabbed my Japanese 625 Word List, and instead of learning the words with pictures and personal connections alone, I took that word list to a few tutors on iTalki, and began taking a couple of hours of tutoring every week (at $4–8/hr!).

In every session, we did one thing: we created simple, personal sentences using the words from the 625-word list.

The first page of the 625-word list has: Earth – sky – up – moon – 1 – white – dot – star.

And so, we took those words and created simple sentences with as many personal connections as I could stick in.

I’m Gabe. I live on the Earth. I look up into the sky, and I see the moon. Next to the moon is one white dot. It is a star.

We’d create a sentence, and we’d talk about which word is which, and how they’re interacting. We’d then play with the sentences until I really understood how they worked:

I’m Gabe. Ok…what about “You’re Azusa“?

I live on the Earth. Ok…can we say, “I live on the moon“? How about “I don’t live on the moon“? Can I use the same construction to say “I live in Los Angeles”? How about “You live in Japan“?

I’d do these tutoring sessions in Skype, and I’d use a call recording app to get an audio recording of the whole session.

Every time we generated a new sentence with interesting new content, I’d have my tutor write it out in the Skype chat window, and I’d copy it to a text editor, along with any other notes I had about our session.

Then, once we’d created sentences for 45–50 minutes, we’d go back and record full speed recordings of each sentence for the last 10 minutes, and I’d write down the time codes of each recording next to each sentence in my text editor. That gave me clear recordings of each sentence, let me review them one last time, and also made it a lot easier to find the recordings of those sentences when I wanted to put them into my flashcard deck.

Over the next 2–3 days, I’d go through my notes for my sessions and turn the sentences into flashcards. I’d learn the words using New Word flashcards, I’d make Word Order flashcards whenever the sentence order was surprising, and Word Form cards for verb conjugations and noun declensions, when appropriate.

And every day, I’d study my flashcards in Anki, effectively memorizing every single thing we talked about.

I would use a simple audio editor to find the recordings of each sentence, and place those recordings onto my flashcards as well.

If something didn’t make sense to me – Why is this verb listed in my word list as X, but it’s showing up in these examples as Y? – then we’d talk about it in my next tutoring session, and I’d ask for additional example sentences using forms X and Y. Then we’d play around with the examples, until I understood what was going on.

What I found is that I was learning very fast, and the words were much more memorable than the simple picture cards I was used to. I was consciously making sure my example sentences were personal, containing stories from my own life, and so they already contained the Personal Connection that I try to add to my early simple picture cards.

They also contain an additional personal connection – my tutor and I personally played around with every one of these words, until I understood how they worked in the context of a sentence. Every time I see my flashcards and hear a recording of my tutors saying a sentence we created, I recall the time we spent creating that sentence together.

And now, rather than just having words I could point to and name, I had words that I could actually use in a sentence. By the time I hit word ~100 in my word list, I found that I was depending less and less upon my tutors to create new sentences on their own. I could do it myself, for the most part, and rely upon them to correct me or supply missing words.

The really nice thing that’s come out of this process is that I now have a fairly intuitive ability to make grammatically correct sentences in Japanese, and I haven’t yet opened up a grammar book. I’ll probably do that at some point in the next few months to try and fill in some details or catch some holes in my knowledge. But all in all, this has been spectacularly effective, and a lot of fun.

So now what?

I don’t think I’d change my recommendations in my book for a first-time learner. One of the nice things about the step-by-step approach of Fluent Forever is that it’s pretty easy to follow, which can help a first-time learner get their feet wet in all of this flashcard business without becoming too overwhelmed.

I think it’d be fairly challenging to jump straight into learning grammar with your very first words if you’ve never learned a language in this way before, and especially if you’ve never used Anki before.

But for folks who have now built up some experience with these methods, or for people who really like understanding a method through-and-through before actually using it, I think this modified approach can be extremely rewarding.

Tools

Update: The below section contains information about using Anki to make flashcards and iTalki to find a language tutor.

Remember, you can now download the Fluent Forever app to automate and speed up flashcard creation for faster progress in your target language.

Next, you can sign up for Live Coaching to practice with a native-speaking tutor who’ll take you to fluency in record time.

To do this, you’ll need a really solid understanding of the methods presented in Fluent Forever. You need to understand how to learn grammar using the flashcard models presented in the book, and you need to understand how to use the All Purpose Card in the Anki model deck.

Next, you’ll need to get a tutor. iTalki seems to have the most options and they seem to be cheapest, so I’d generally recommend finding someone there.

You’re looking for a native speaker of your target language who is also nearly fluent in an additional language that you speak well. For most of you, that means finding someone who speaks English, who can help you translate personal stories into your target language, and who can help you find ways to use example words.

Try out a few tutors and see who seems to understand what you’re trying to do. You may find that some tutors have their own teaching styles and lesson plans, and don’t enjoy translating. Thank them for their time and move on to someone else.

You’ll want Skype – most international audio or video chat is done through that platform. And you’ll want a Skype call recorder. Skype has a list of recorders here.

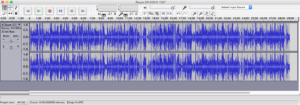

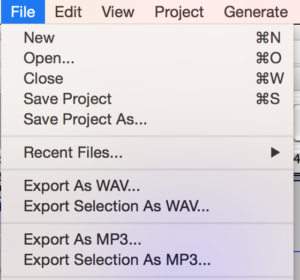

Once you make those hour-long recordings, you’ll want an audio editor to chop them up into little, single-sentence chunks. Audacity is free and should work just fine.

Mostly, you need an editor that allows you to find the recordings of each sentence – you should be able to see the whole audio stream with time codes on top – select the sentence, increase the volume when needed, and export that selection as an mp3.

On my Mac, I’ve been using a slightly expensive ($60) combination of a call recorder and audio editor, namely Audio Hijack (for recording calls) and Fission (for editing audio). I like the interface for those tools and find them worth the extra money.

Next, either grab the free word list here (use the alphabetical one, so you don’t run into order-related problems) and have your tutor translate it. Alternatively, use one of my translated lists and start making sentences with your tutor.

During your session, make notes in a text editor. Towards the end of your session, ask your tutor to say each sentence that you created one more time, at a relatively fast rate of speed – the speed they’d use in a normal conversation.

While they’re doing this, keep an eye on your call recorder’s timer and write down the start time of each sentence, so you can find it later on.

Once your session is done, go back through your text notes and start making flashcards for every new word in every sentence, every surprising word form, and every time the word order surprises you.

Grab pictures off of Google Images, either searching in your target language (if your language has a strong internet presence and you’re searching for an easy-to-visualize word), or just searching in English.

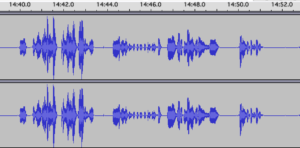

Last, put a recording of the sentence you’re working on on the back side of your flashcards (in the “Extra Info” section of the All Purpose Card). To do this, open up your recording in an audio editor.

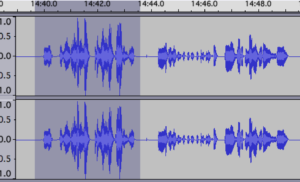

Then, zoom in until you can see the silent moments between each sentence. You’ll want to see 10–30 seconds on your screen at once.

Select the sentence and export it as an mp3:

Then find that file on your hard drive and drag it into the appropriate field of your flashcard (the “Extra Info” field, if you’re using my All Purpose card.)

Tip: If you have a long string of sentences that link all of your words together, like the examples above for Earth – sky – up – moon – 1 – white – dot – star, only put ONE sentence at a time on your flashcards. Otherwise, it takes too long to listen.

Final notes – on languages with limited resources

One of the really nice things about this tweak is that it doesn’t require ready-made resources – you don’t need a good grammar book or movies or audiobooks. You don’t even need your language to have a strong internet presence (as long as you can still find a tutor).

All you need is a native speaker who’s willing to help you develop your own resources. And the resources you develop are going to be personal, so they’re way more memorable than your standard language learning fare.

Effectively, this means that if you’re learning a language with limited resources, you’re no longer at a disadvantage.

That’s all for now! Enjoy, and post questions and comments below!

Make your flashcards faster

If you want to save yourself ~30–60 minutes of time making your first Anki flashcards, then check check out our shop, which has a number of resources you can use to speed up the process. There are also other ready-to-use Anki flashcards in various languages that you can check out.

Don’t forget that we now also have our Fluent Forever mobile app, which doesn’t use Anki but can be way faster. Download it here to get started.

For more tried-and-tested tips to speed up your progress to fluency, check out our comprehensive guide on The Fastest Way To Learn a Language Forever.

[shareaholic app="share_buttons" id="28313910"]